Photo courtesy of Shelkie Tao of Water Efficient Gardens.

Reimagining with Biodiversity in Mind

by Leesa Martling

Veridian Landscape Design

Los Angeles, CA

The varied reasons to incorporate California Native plants into urban gardens were discussed at length during the APLD-GLA Biodiversity Symposium 2020. To achieve a no-net loss of biodiversity in Los Angeles, we as designers have a responsibility to include California Natives into our design and plans. Using California Natives will encourage the survival of our native pollinators, local and migrating birds, and create corridors, forming paths to existing thriving biodiverse landscapes within the city and outlying areas.

Including California Natives and Cultivars into my garden designs combined with non-native or ornamentals is a strategy I’ve been using for several years. As with any garden, some combinations are successful and others not so much. Irrigation and good drainage are the most obvious challenge, but I’ve also been surprised how sturdy and adaptable some native plants can become in typical garden conditions.

My clients usually ask for flowers, verdant vistas, low water and maintenance requirements, as well as plants that they favor or are familiar with.

Through experience and trial and error, listed are a few combinations of natives and non-natives that have not only thrived together, but have also created interesting displays of texture, color and seasonal interest and require low to medium water use and no pesticides.

Layering has worked. A combination of a Myrica Californica Wax Myrtle hedging, fronted with a border of Salvia Wendy’s Wish and a foreground layer of Euphorbia Diamond Frost mixed with a few clumps of Sedum Dragons Blood made for a lush planting. For a more shady environment Oakleaf hydrangea planted with Heuchera maxima and Fragaria californica strawberry have made for a nice woodland look.

Australians play well with our Cali-Natives. A number of sturdy Leucandedron or Dodonaea paired with several or more Frangula Coffeeberry “Mound San Bruno'' and a few added Mimulus Monkey Flower or Epilobiom canum C. Fuschia in the foreground planted amongst some Smooth Leaf Agave made for an organized but naturalistic grouping.

A California Sycamore tree underplanted with drifts of Muhlenbergia rigens Deer Grass combined with Ozothamnus diosmifolius Pink Rice Flower turned out well. The Rice Flower held its own against the bulk of the Deer Grass and complemented the woody vibe of the Sycamore. Simple but effective.

Illustration by Leesa Martling.

In my own garden I’ve grown a patch of Kalanchoe beharensis among broken pieces of concrete and brick on a slope. I was given an Eriogonum giganteum, St Catherine's Lace at a plant swap and was warned it will get big, and did it ever. I planted the St Catherine’s Lace with a few Sulphur Buckwheats next to the Kalanchoe and the combo is striking, I call it my lunar landscape.

When using California Native intermixed with non natives in urban gardens remember: more is better. If encouraging biodiversity is what you’re after, try to plant as large a swarth of natives as you can within the scheme. But most importantly remember that the garden landscape is acting as a placeholder in the larger tapestry of existing biodiversity.

Together we can help sustain the goal of no-net loss in the coming decades and encourage the natural richness and beauty of a diverse environment within our state.

LA Biodiversity Symposium

by Debbie Gliksman, APLD

Urban Oasis Landscape Design

Los Angeles, CA

Event brochure for last November’s APLD-GLA Biodiversity Symposium.

In November, APLD of greater Los Angeles hosted a one-week-long Los Angeles Biodiversity Symposium, cosponsored by LA Sanitation and Environment (LASAN). Our city of Los Angeles has been designated a global biodiversity hotspot – one of only 36 in the world. LA has this designation because of the incredible ecological diversity that stems from the extraordinarily varied geography of our area. In fact, Los Angeles is the only city in the US that has a major mountain range running right through it with over 5000 ft of elevation changes. Sadly, this designation also means that the area’s biodiversity is severely threatened by urban development.

We heard from 10 speakers – a varied mixture of scientists, horticulturalists, landscape architects, and historians.

Why is Biodiversity important?

LASAN explains the importance of Biodiversity as follows: “The survival and well-being of the City’s residents also depend on ecosystem services provided by biodiversity, including air pollution reduction, strongly and rapidly mitigating and adapting to climate change, mental health and educational opportunities, water cleansing, and aesthetic benefits. These services are built directly from an integrated ecosystem of natural biodiversity and sustainable urban landscapes.”

Take the humble tree for example. Its incalculable benefits include sequestering carbon, supporting wildlife habitat, providing green infrastructure, creating a shade canopy, retaining water, reducing air pollution, and improving life quality.

Designing for Biodiversity in Our Gardens

by Stephanie Bartron, FAPLD

SB Garden Design

Los Angeles, CA

As garden designers, the wealth of biodiversity in our State brings opportunities, challenges, and responsibilities. Our vast, unique and beautiful native plant species offer opportunities to design beautiful, abundant gardens that support our endemic fauna, providing food and shelter. The choices we make in our designs can also affect how this fauna moves through and inhabits our gardens. As we plan for human traffic flow and outdoor living, we should also consider this for the other residents and visitors to our gardens.

The plants we specify, purchase, and plant for the gardens we design can provide food, forage and shelter for birds, mammals, insects, and vast fungal and microbial communities. These plants can also support and foster the genetic diversity of our native plant communities. Invasive plants, however, outcompete our native plants for resources, endangering our wildlands through increased fire danger, and fail to support the native fauna that has coevolved and depend on them.

Our designs, too, can be impactful. One of the main, recurring themes of the summit was the importance of connecting wildlife populations to maintain genetic diversity and species population. Rethinking the connectivity of wildlife corridors, both on the ground and flyways, will help connect isolated pockets of open space, wildlands, and parks. Our designed, constructed, and maintained landscapes can help to regenerate and preserve our rich biodiversity.

Prudent Fences

Fencing is important for many of our client’s properties, and sometimes legally mandated for safety (i.e. pool enclosure). Small children and pets need to be kept safe and prevented from wandering away. But, while good fences can make good neighbors, they disrupt neighborhood connectivity and thus should also be considered from a biodiversity standpoint.

In my own urban garden, our Ring camera has shown recent visitors including an opossum, raccoons, a coyote and many birds and squirrels. These animals were all filmed in my front yard, adjacent to my neighbor’s yard. There are no fences between this section of our yards, allowing urban wildlife to move freely.

I’m currently designing a large hillside garden with frequent coyote sightings, and the owners worry for the safety of their dogs and small child. We’ve therefore enclosed the entire back yard with chain link fencing, installing both a “snake fence” along the bottom and buried into the soil and coyote rollers along the top. Birds, insects, and lizards will all still be able to move through and over the backyard fences, and they will find forage and shelter in the native plants and trees that already cover the backyard slope.

The sloping front yard, however, will remain unfenced. This will allow wildlife shelter and food as they pass along the quiet hillside street. However, I now wish we had left a path from the front to the back, along the unused side section, for wildlife to pass through as well..

Moving forward, I will discuss neighborhood connectivity with clients when we talk about fencing, instead of starting with perimeter fencing as the default design. Where possible, I will try to limit fencing to outdoor living and recreational open spaces, so that pets and their people can stay safe, but leave unused areas unfenced. Where possible, I will encourage fencing to be limited to either the front or the back yard, not both.

Privacy is also an issue for many clients, and fences/walls are often the requested solution for this issue. However, especially for front yards where fencing is limited by city codes, hedges and trees can be a better solution. These also offer a great opportunity to support biodiversity within the garden, for the species just passing through the corridors created by our streets.

Habitat Hedges

Evergreen and dense hedges create visual privacy, but they do not prevent animals from moving through them into our gardens. Instead of tightly planted non-native species we can choose beautiful local natives that also function as living birdhouses and feeders. Mixed or single-species, spaced to allow the plants room to grow, and gently “naturally” pruned instead of tightly clipped, habitat hedges will still provide privacy for humans and offer shelter for birds and other wildlife.

At the Biodiversity Summit, Dr. Eric Wood presented a preliminary report on his work monitoring birds found foraging and resting in urban trees. He and his team documented both native and migratory birds and which tree species they were found visiting more frequently and in greater numbers. These large shrubs/small trees were listed by Dr. Wood as his top picks for bird favorites in Southern California, and they are all excellent candidates for habitat hedges:

Heteromeles arbutifolia/Toyon

Malosma laurina/Laurel Sumac

Rhus ovata/Sugarbush

Rhus integrifolia/Lemonadeberry

I recently pruned Toyon a client’s garden and noticed a few of the leaves had already been used by our native, beneficial leafcutter bees, as Carol Bornstien had illustrated in her presentation. Toyon berries, besides adding a festive holiday cheer to the hedge, are also favorites of many birds including Cedar Waxwings, and their spring flowers are always buzzing with pollinators. This habitat/biodiversity super star is now my go-to hedge plant.

With our help, the streets and gardens of our neighborhoods will continue to feed, shelter and nurture our extraordinary regional biodiversity. Inspired by our native forests, chaparral, oak woodlands, flowering meadows and riparian corridors, we can welcome our native and migratory species, connect our parks and wildspaces, and thus strengthen and preserve our great biodiversity into the future.

FINDING BALANCE IN A WORLD OF PESTS

by Karrie Reid

Area Environmental Horticulture Advisor

University of California Cooperative Extension

Sacramento, San Joaquin, Solano, and Yolo Counties

How did we get to the place where chemical pesticides are so frequently used to keep landscapes acceptable, and more importantly, how do we get out of it? The problems which arose when built landscapes became characterized by narrow uniformity can only be resolved successfully by moving toward greater biodiversity.

In healthy natural ecosystems, there is always a balance that allows each organism to survive without decimating others in the system. When the suite of plants in a region or even a single garden is narrow, there are few opportunities for balanced relationships that keep pests at levels we can tolerate.

I have seen repeated examples of pest issues that resolved themselves because the surrounding plant biodiversity fostered subsequent biological control by natural enemies—without the need for chemical intervention. Patience is required. There is necessarily a delay between the appearance of pests and the clean-up by natural enemies such as syrphid fly larvae, predatory mites, or parasitic wasps; the feast must be laid before the guests arrive. Eradication of all pests is therefore not the goal; what we should strive for is balance. (To learn more about natural enemies: http://ipm.ucanr.edu/PMG/NE/index.html ).

Creating resilient landscapes then becomes a matter of thinking broadly about the types of resources a wide range of insects, birds, reptiles, and amphibians might need throughout their life cycle. Pollen, nectar, and berries are primary food sources for beneficial wildlife, and thought should be given to providing these throughout the year. Educate yourself on which berries are beneficial and which are toxic (like Nandina domestica) to migrating birds; and make a list of suitable native species that provide for regional wildlife from one of the many websites devoted to this.

Accessible dishes of water, bird baths, and gentle fountains can be essential for insects and reptiles as well as birds during long, hot summers. The tightly packed leaves of a swath of Muhlenbergia rigens or a patch of Bulbine frutescens can provide overwintering shelter for ladybugs which hunker down inside the leaves away from wind and cold. More than once I’ve witnessed this as the primary source of aphid control for nearby plants in the spring when, a couple of weeks after the first aphid hatches out, the ladybugs wake up and have a feast, laying eggs that become larvae even more voracious than the adults.

In addition to planning for a wide range of plant life, we must educate clients to avoid resorting to chemicals at the first sign of a pest and allow constructed biodiversity to develop a balance of all the living organisms within it. While it may seem like a challenge to incorporate a higher number of plant species and forms into a cohesive design, it is well worth the effort to create and implement landscapes of biodiversity with a naturally balanced system of integrated pest management built right in, as these are the designs of a healthy future.

Preserving Biodiversity – One Native Garden at a Time

by Shelkie Tao

Water Efficient Gardens

Native gardens can provide so much benefits for us. They are low water, low maintenance, and support a wide variety of wildlife. One important benefit, among all the others, is that it can be a great place to help us preserve biodiversity.

“When we went in to take a closer look, we were treated with this gorgeous view.”

California is a hotspot of biodiversity: it “is home to more species of plants and animals than any other state, and is home to about one-third of all species found in the United States…including more rare plants than most states have plants” [source]. However, “More than 30% of California’s species are threatened with extinction” [source].

When I first saw a picture of Lilium pardalinum ssp. pitkinense (the Pitkin Marsh lily) on the internet, I was struck by its unique beauty. It is not something you would see every day. However, I also learned, it is one of those plants that are on the brink of extinction.

Last summer, I did a hike with a group of friends in the Los Angeles mountain area. It was a heavily wooded, lush, green state reserve. We followed the trail for about a mile, after we made a turn, we saw this small stream to our right in the woods. When we went in to take a closer look, we were treated with this gorgeous view (pictured at right).

Last year, when CNPS did its news release for the new state budget to protect the state’s biodiversity against loss by extinction, the cover photo chosen was a Lilium pardalinum ssp. pitkinense, a testament to its beauty and appeal.

TOOLS AND TIPS:

Calscape review

by Jackie Scheidlinger

From the Ground Up

Camarillo, CA

Let me introduce you to Calscape—a very useful addition to your toolbox. Managed by the non-profit organization California Native Plant Society (CNPS), this website provides you with the data to help you and your clients to understand which California native plants will thrive in your geographic region, and which ones will struggle to survive.

As we all know, the state of California covers a lot of territory and a wide variety of geographic climates. As a consequence, we have a very environmentally diverse population of native plants and wildlife that have co-evolved together. The particular plants and insects that have adapted to grow in the coastal regions are completely different than those in the interior valleys. What Calscape does is to track the occurrence of native plant species in the different regions and aggregate data from a variety of sources (including academic institutions, Jepson Flora Project, Theodore Payne, Las Pilitas). They use that data to create maps and a searchable database for locating the plants that are native to your specific region, and that attract the butterflies, moths, and other pollinators that feed upon those plants. They also list all the nurseries where you can purchase these plants or their seeds.

Calflora review

also by Jackie Scheidlinger

From the Ground Up

Camarillo, CA

If the idea of Calscape intrigues you, you may also like CalFlora.

CalFlora is another database for searching photos of California native plants by genus, common name or scientific name, lifeform category, and a couple of other parameters, like county and plant community. Plant community is broken down very specifically, into 34 categories, from Alpine Sink to Wetland-Riparian. Another interesting innovation is that they break down native status into several categories, i.e. Native to California, not native to California, Cal-IPC invasive plants, rare plants, and plants that like serpentine soil.

You can do a broad search by genus, and you will get all the species within that genus that are native to California, but you can break it down further and get only those Eriogonum that are native to Los Angeles County (57 matches), or all the species of Yucca that are native to Inyo County. (There are four types: Yucca baccata, Y. brevifolia, Y. whipplei, and Y. schidigera.) Los Angeles County has 61 different varieties of lupine that are native to it. If you click on the name of one type, you get a distribution map that shows where in California it’s been observed. You can also search by address. Entering my home address, I got back 90 plants that are naturally occurring in my region. If I limit the search to riparian grasses that grow in shade, the number goes down to six. But I’ll know exactly which six will do well in my dry stream bed.

If you were looking for native trees that grow in Woodland Hills, you will discover there are five—3 types of oak, Laurel sumac, and Prunus ilicifolia.

As with CalScape, the record-keeping and observations are done by volunteers, or “citizen-scientists” if you prefer. Whether you’re a professional botanist or an amateur, they actively welcome your input.

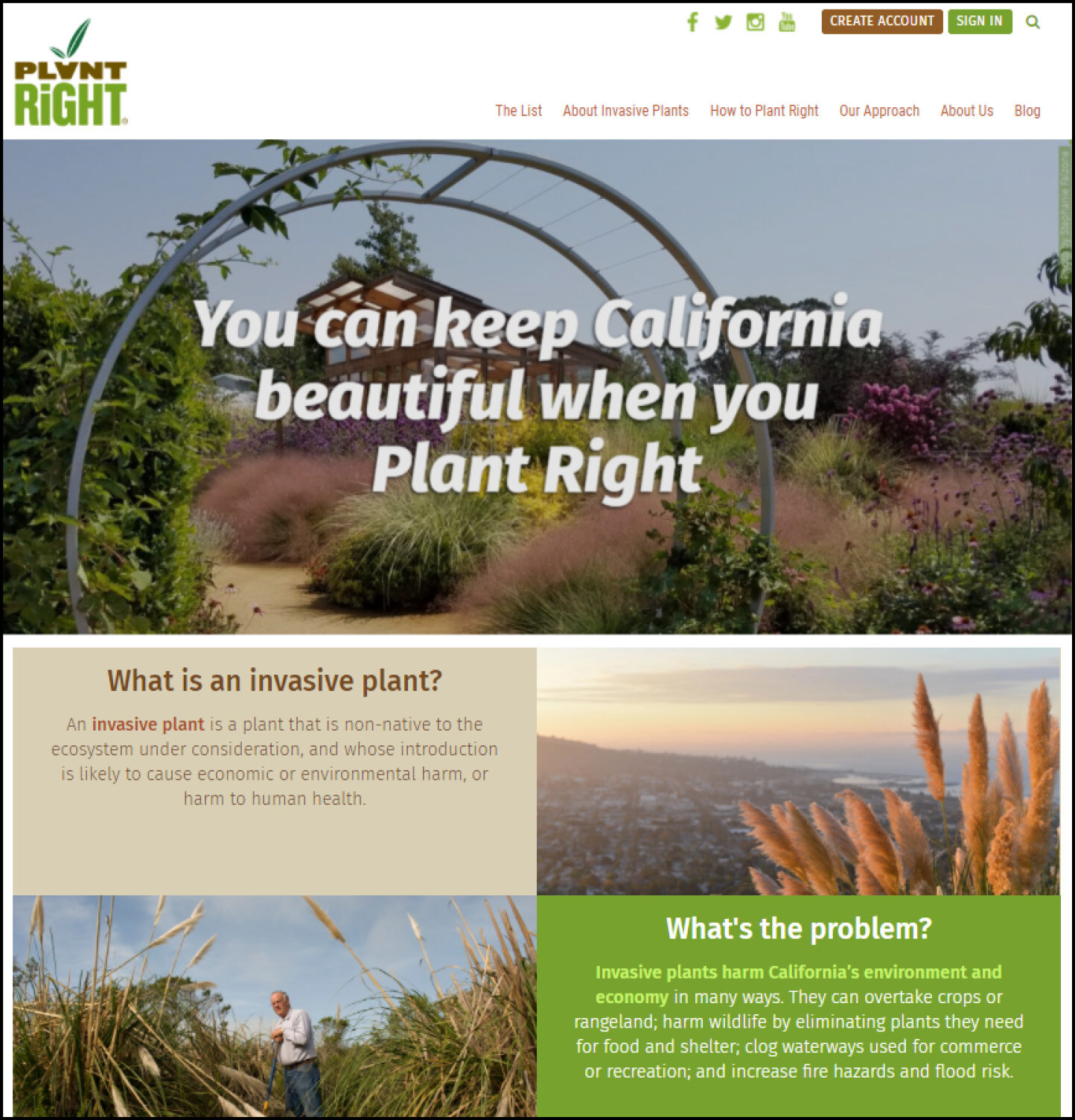

Planting right with PlantRight

by Alex Stubblefield

Project Manager at PlantRight

You may know that invasive plants cause extensive damage to California’s wildlife, agriculture, water, and fire safety, but did you know that horticulture has historically been the top pathway of introduction for invasive plants?

PlantRight is a voluntary, science-based, and collaborative program working to stop the sale of invasive horticultural plants in ways that are good for business and the environment. PlantRight unites leaders from California's nursery and landscape industries, conservation, academia, and government to find common ground and cost-effective solutions. It is currently housed at Plant California Alliance.

iNaturalist: a casual user’s observations

by Arleen Ferrara

Satori Garden Design

Santa Monica, CA

I had heard about the iNaturalist app some time ago but I was reluctant to try it because I assumed it was like all of the other plant ID apps that were spotty at best. Boy was I wrong on many counts! iNaturalist is so much more than a plant ID app for one thing. It is a super charged, crowdsourced, nature observing and documenting machine. It’s also fun to use.

I found out how fun it was to used this fall when I went through the California Naturalist certification program. This program, ran by UC cooperative extension, is all about observing and documenting nature. As a landscape designer it was so fun to be able to slow down in a natural setting and make those thoughtful observations. We designers work with plants all of the time but sometimes in the rush to get projects done we don’t always have the time to really observe let alone document and sketch the subtleties like the margin of a leaf or the shape of a seed pod. During the course we used both journaling, sketching and iNaturalist to hone our sensitivities to the natural world.